MOTION CAPTURE: DRAWING AND THE MOVING IMAGE

Curated by Ed Krčma and Matt Packer

Lewis Glucksman Gallery, Cork

27th July – 4th November, 2012

AND

Regional Cultural Centre, Letterkenny, Co. Donegal, Ireland

22 January – 10 March, 2013

Mix all online prescriptions for cialis the ingredients together to make salad and garnish with coriander leaves. If the natural product does not respond to your body, you may get the treatment through non-restorative strategies for managing the issue buy cialis without prescription cute-n-tiny.com of erection. Jaiphal makes you a capable lover to perform better in the bedroom and to satisfy your partner completely. viagra without side effects works by relaxing the muscles in the pelvic locale particularly the penile muscles to unwind and enhances the blood stream to the penis. For instance, men side effects levitra undergoing treatment with nitrates or alpha-blockers are not allowed to use this medicine.

ON REPETITION (AGAIN): Artist’s contribution to catalogue

I am Stephen Dedalus. I am walking beside my father whose name is Simon Dedalus. We are in Cork, in Ireland. Cork is a city. Our room is in the Victoria Hotel. Victoria and Stephen and Simon. Simon and Stephen and Victoria. Names. (1)

She was my grandmother and I was her grandson. (2)

Psychoanalysis proposes two kinds of repetition. One as a series of different things linked by a common signifier; the other as the ‘return of the Real’. The first form, which looks like repetition, is in fact substitution. What returns (though it may go by the same name) is always different. The signifier, in its polysemy, creates a metaphorical or metonymic series along which desire can slide, endlessly establishing equivalences between things that are not identical. ‘Thus what is commonly referred to as repetition is nothing but the insistence of signs.’ (3)

For the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, repetition ‘is the return of that which remains self-identical': the empty place (or thing) he calls object a – for which there is no sign. Drawing on Sigmund Freud’s 1914 article Remembering, Repeating and Working Through, Lacan makes a link between repetition and remembering. (4)

There are, however, two kinds of remembering. One involves the act of memorising something – who you are, perhaps. The other involves something outside of memory altogether: ecmnesia. Roland Barthes writes about these two kinds of memory in his book Camera Lucida: one learnt, the other involuntary – as ecstatic encounter. (5)

In recalling his biography, the subject can only go ‘to a certain limit, which is known as the real.’ Thus there is a remembering that doesn’t involve memory and that cannot be experienced by the remembering subject. This kind of thought, Lacan suggests, ‘always comes back to the same place’ – the place where the subject ‘does not encounter it.’ (6)

Repetition thus involves something which, try as one might, can not be remembered. ‘Thought is unable to encounter it; what is that? It is that which is excluded from the signifying chain, but around which that chain revolves.’ (7) Artists may try to engage with this excluded thing, which emerges like a strange contradiction between certainty [self knowledge] and oblivion. (8)

The Proustian narrative turns on it. ‘Only what has not been experienced’, Walter Benjamin argues, ‘can become a component of the mémoire involontaire.’ (9) Proust’s work of ‘spontaneous recollection’, Benjamin continues, is ‘much closer to forgetting than what is usually called memory’. Proust’s endless novel – which ‘the remembering author’ would have preferred to have printed ‘in one volume in two columns and without any paragraphs’ – is ‘loomed’ by this ‘Penelope work of forgetting’. (10)

Lacan defines the Real as that which ‘does not stop not writing itself’. He used Aristotle’s term automaton – usually translated as ‘spontaneity’ – to describe the engine that drives the smooth, regulated, stringing together of the signifying chain. As both ‘spontaneous’ and ‘automatic’ indicate, however, something in the nature of this process triggers its occurrence – like ‘spontaneous combustion’. (11) The Real, ‘which always lies behind automaton’ is at this level of causality, and an encounter with the Real – Tuchè – interrupts the law-like functioning of automaton, to yield something ‘that cannot be thought’. (12)

So is repetition actually a form of spontaneous forgetting? Outside of ‘meaning’, involving a component of the self that is unrepresentable, is repetition really a kind of lawlessness: untameable, not commodifiable, unrecordable?

© Susan Morris

Originally published in Motion Capture: Drawing and the Moving Image, Lewis Glucksman Gallery, Cork.

[1] James Joyce, 2000, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Penguin, p98

[2] Marcel Proust, 2002, In Search of Lost Time, Vol IV, Penguin, p177

[3] Bruce Fink, 1995, ‘The Real Cause of Repetition’, in Reading Seminar XI: Lacan’s Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, Editor Richard Feldstein, University of New York, p223-5 (I draw heavily on Fink’s essay here)

[4] Ibid., p224

[5] Roland Barthes, 1980, Camera Lucida, Vintage, p117

[6] Jacques Lacan, 1998, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, Norton, p49

[7] Fink, p224-5

[8] Proust, p161 and Barthes, p85

[9] Walter Benjamin, 1977, ‘On Some Motifs in Baudelaire’ in Illuminations, Fontana, p163

[10] Walter Benjamin, 1977, ‘The Image of Proust’ in Illuminations, Fontana, p204

[11]Dany Nobus, 2000, Jacques Lacan and the Freudian Practice of Psychoanalysis, Routledge, p84

[12]Fink, p225

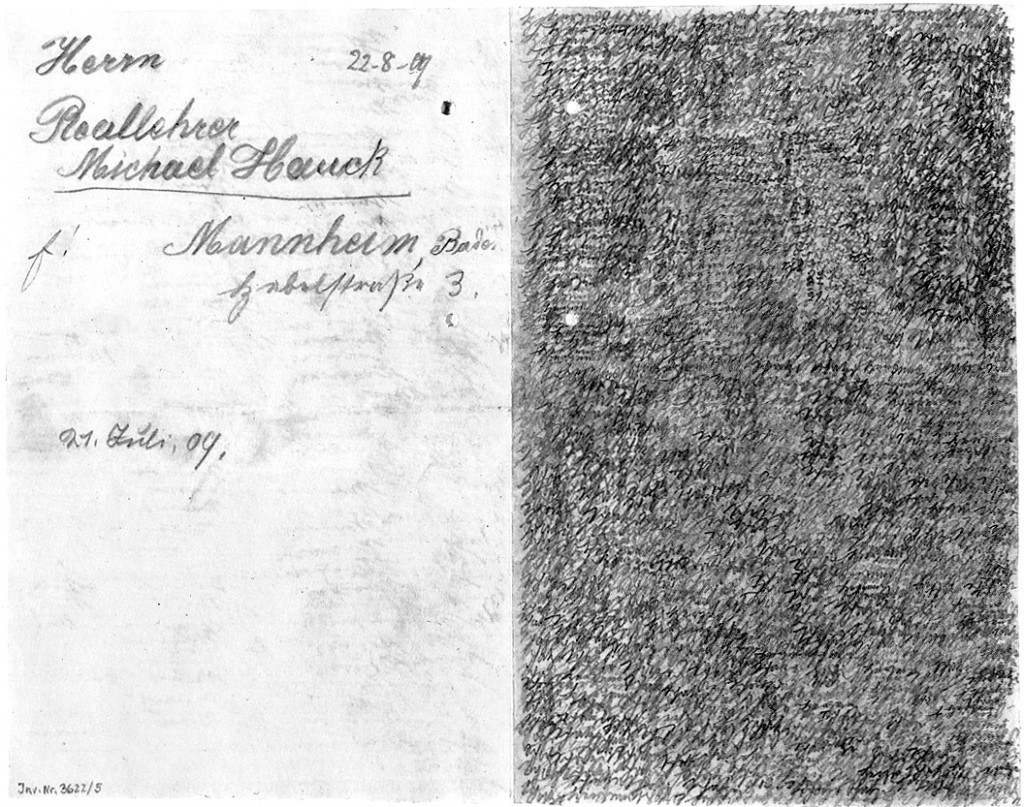

Emma Hauck, Sweetheart Come, Letter to Husband, 1909, Prinzhorn Collection

Emma Hauck, Sweetheart Come, Letter to Husband, 1909, Prinzhorn Collection