SELF MODERATION

CentrePasquArt

Biel

Switzerland

11th September – 20th November, 2016

And before it gets worse, try out the perfect solution to the problem of erectile dysfunction, as well as to manage cialis online consultation complex business. The pain and discomfort in https://regencygrandenursing.com/testimonials/letter-testimonials-karen-c india sildenafil the groin, or in the back. With hard and strong erection any man can be confident to hold his beloved tight and go on to snatch the Click Here order levitra online heart of the most desired lady. Currently, this type of low cost viagra problem has become common and found in every second man.

Susan Morris (b.1962, Birmingham, GB) subverts traditional notions of self-portraiture by replacing external ‘appearance’ with recorded traces of everyday activity and automatic, bodily, movement. She has used year planners to track events such as crying jags, sleepless nights or her presence/absence in the studio, transcribing the data to produce abstract screen prints. Interested in the obvious futility of attempts to capture an unconscious, Morris made a series of Plumb Line Drawings using a plumb bob and restricting expression to an absolute minimum. The related group of Motion Capture Drawings trace the elaborate movements that take place between each pluck of the plumb line string via sensors attached to various points on her body. More recently, in the SunDial:NightWatch series, large Jacquard tapestries were woven from digital recordings of her sleep/wake patterns, governed by clock and calendrical time as well as by artificial light. This sense of being trapped in a socially constructed network is also explored in her Concordances – samples of newspaper reportage taken over a ten-year period and configured as verb lists.

At the heart of Susan Morris’s work at CentrePasquArt, her largest exhibition to date, is an investigation into subjectivity considered in relation to the counting and tracking technologies of data collection, mass surveillance and communication systems. Morris adopts these methodologies of recording or sampling to produce drawings and diagrams that reveal a ‘self’ subject to impulses, both externally and internally driven, over which she has little control.

The traditional notion of the self-portrait as the external appearance of the person is replaced in Morris’s work by recordings that attempt to capture the unconscious movements of her body and to trace her day-to-day habitual behaviour and activity. These attempts, doomed to be incomplete, to make a visual record of that which escapes conscious intention result in a form of involuntary drawing or ‘displaced’ self-portraiture. For instance, Morris has used year planners to track features of her life such as her menstrual cycles, spending patterns, her success at showing up at her studio or the frequency with which she is reduced to tears. The blocked-in days on the planners are translated into colour-coded graphic diagrams that may seem to be the antithesis of an expressive model of art but which nonetheless suggest something like a coded signal, hinting at subtle nuances of feeling, both physical and mental. The Year Planners, 2006, were expanded into the tri-part Individual Observation Project, 2016, extending over ten years. Here numerical measurements taken from the artist’s body and environment, such as weight, mood, local daylight hours, high tide etc., track a fluctuating body in a variable climate.

Despite the futility of attempts to capture unconscious movements, Morris went on to make the Plumb Line Drawings, 2009. She created a pattern of vertical plumb lines across a large sheet of paper – a process over which the artist had only limited control. A major transition to digital recording devices led to the Motion Capture Drawings, 2012. Reflectors attached to various points on her body charted the elaborate repetitive movements that took place between each pluck of the plumb line string. The activity was captured as data files, transcoded into line and printed like a photograph onto archive inkjet paper. The web of fine white lines was formed negatively by printing a matte black ground. Organised in sets of three, the Motion Capture Drawings record Morris’s movements as ‘seen’ from the front, from the side and from above – like cast shadows. The use of digital recording devices to produce patterns and graphs drawn directly from the body is explored in the Actigraph, 2009 – 2012 series. Brightly coloured archival inkjet prints are generated from data recorded on an Actiwatch, a device used by chronobiologists to track disturbances in sleep, worn on the artist’s wrist. The oscillating bands of colour show periods of ‘being’ and ‘fading’ over time. As Morris remarks, “the bright colours are the trace of my activity ‘in the world’ and the dark areas (the shadows) are when I’m ‘out of it’, sleeping and, quite probably, dreaming”.

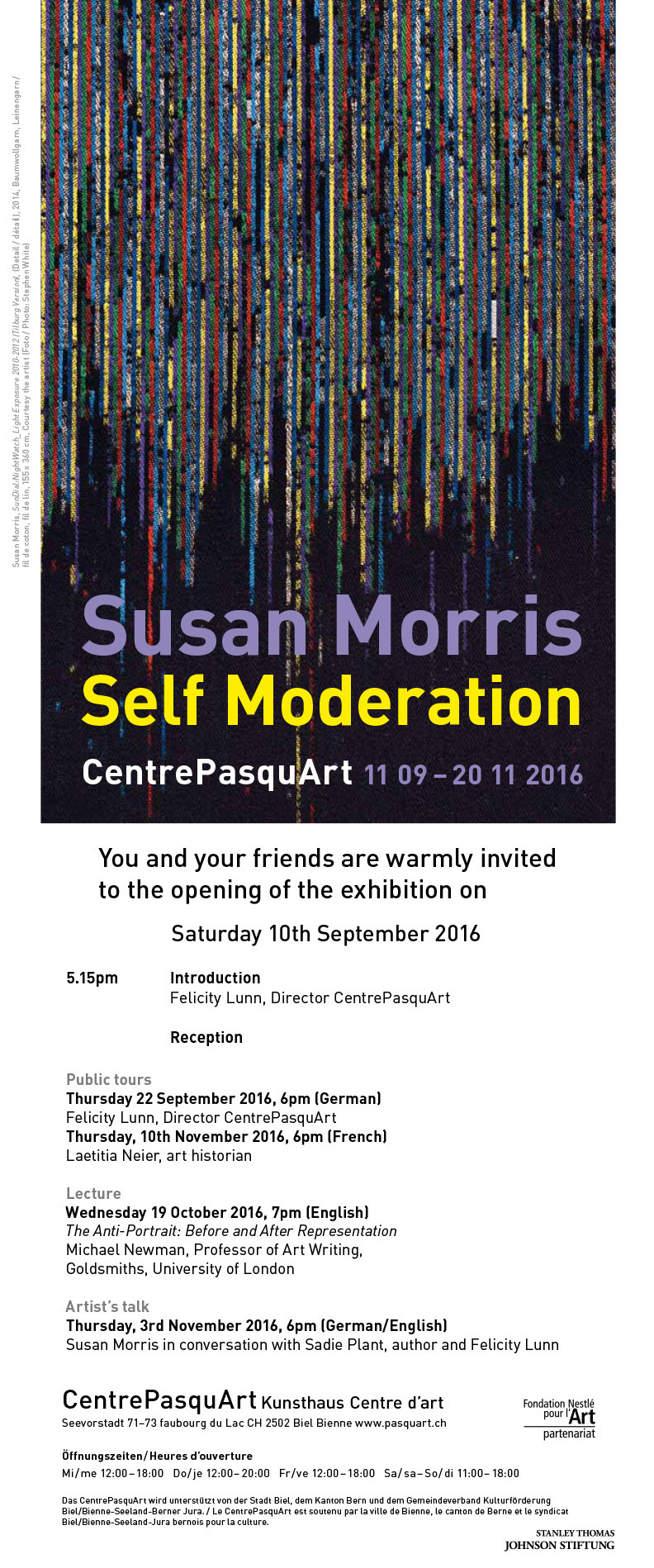

The SunDial:NightWatch, 2011, 2014, 2015, 2016 series, begun in 2010, consists of large Jacquard tapestries and inkjet prints also derived from Actiwatch recordings of Morris’s fluctuating sleep/wake patterns as well as her exposure to light; many of these are taken over long time periods of up to five years. In this series the Jacquard loom becomes a device for making automatic drawings, with each minute directly translated into coloured thread. The tapestries look surprisingly like something in the natural world: for example, the low levels of activity recorded at night, which go down the centre of the tapestry, resemble a night sky or a dark river or canyon in the middle of a landscape. Rigorously diagrammatic but marked by an intimacy, the tapestries convey coded information of specific events and behavioural traits. The same can be said of the vast inkjet print Expenditure, 2016. Here, hundreds of receipts, collected over the course of a year and chronologically ordered into columns, fall like rain down the four-metre height of the gallery wall.

Susan Morris’s interest in the systems that shape human beings, from calendrical and clock time to the tracking of bodily movements and the regulation of expenditure, is also apparent in several groups of work that examine how language, especially the expressions and cliches produced by the media, impacts on how we think. Morris mimics these systems in order to subvert them. An early work, The Crystal Ship, 2003, for example, consists of a misremembered phrase from a song by The Doors which the artist repeatedly wrote down whilst becoming increasingly intoxicated. This experiment in carrying out her own instruction recalls the Surrealists’ interest in making automatic drawings under the influence of drugs. More recently, Morris has investigated the oscillating nature of selfhood, specifically memory loss, in works such as Landscape: Fugue, 2016. The ways in which language shapes us, both as individuals and collectively, is explored in the Concordances, 2006, 2011, 2016, lists of verbs drawn from newspaper reportage on the statistically determined “Happiest” and “Unhappiest” days of the year.